4 Things to Consider When Adopting WebAssembly for Embedded Systems - Part 3 Integration.

I’ve rewritten this blog post about 5 times. The original was much longer. I had a university professor who would say:

“Beware of big books! - They tell you the same things as a small book, but they take a lot more time doing it”.

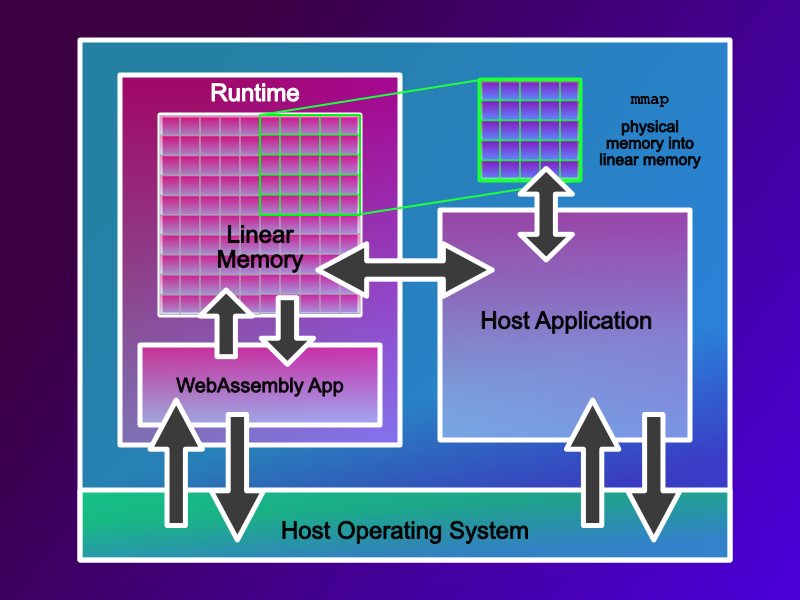

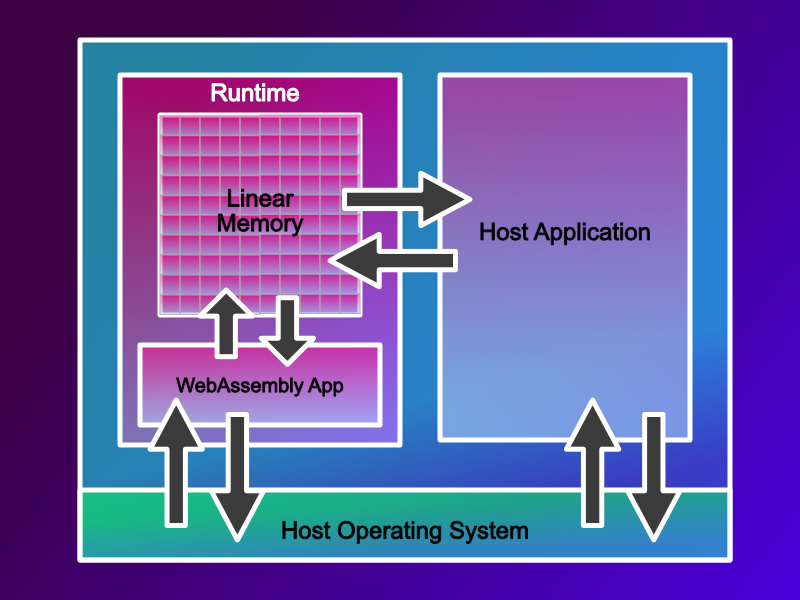

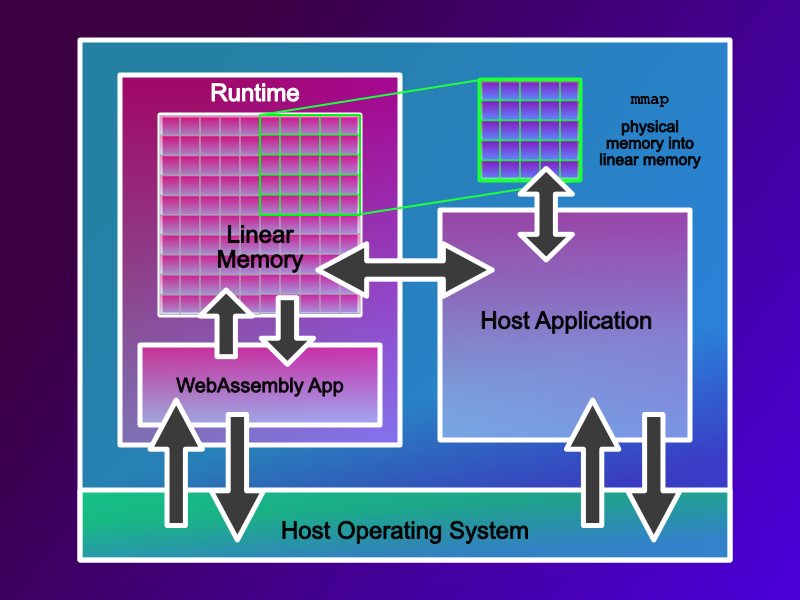

With this in mind, let me try to convey my approaches to the integration of WebAssembly into an embedded device. A huge part of this is actually over coming the sandbox; we need to get sensor and other data into the WebAssembly sandbox and get the decisions made by our WebAssembly code out of our sandbox as quickly as possible. This is important because CPU cycles on embedded devices are scarce, the less time we need to spend moving data about the more time we have to do real work. Many embedded devices are connected to physical machines, reducing this delay results in more responsive, cheaper, safer, and more battery friendly devices.

Getting Data into and out of a WebAssembly Application as Fast as Possible

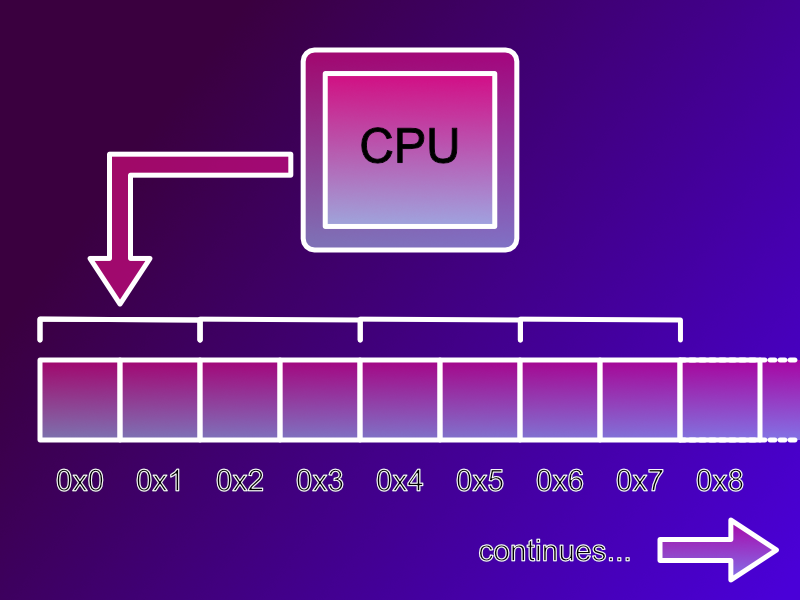

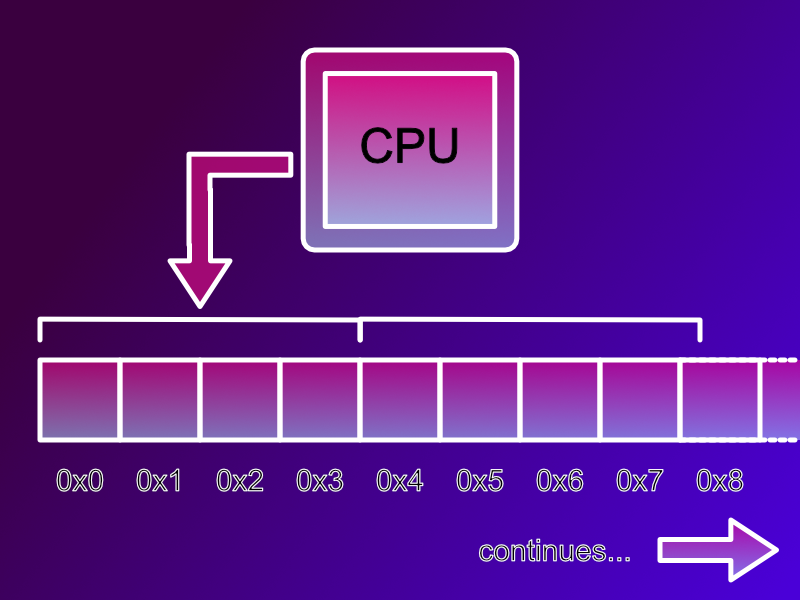

The issue of getting data into and out of a WebAssembly sandbox as fast as possible is something which doesn’t just impact embedded systems, it’s applicable to many. So, how do you do it? - Well the answer is surprisingly easy. Let’s think about our limitations; the host can read and write linear memory, the Wasm application can read and write linear memory but cannot access any other memory space. The answer, therefore, is to share access to Linear memory.

If you’ve an area of memory you want your WebAssembly application to access, but it is not in Linear memory, then if you have an MMU, mmap your required memory area into linear memory. If you don’t have access to an MMU, then you are going to need to copy the data into and out of linear memory.

Pretty simple. It just relies on WebAssembly and the Host having an easy to understand binary format that they can all use. And they do. It is the Linux application binary interface format, or Linux ABI. If your host system is a Linux system, this makes integration pretty straightforward. Let me explain.

Binary Formats and Data Copying

There are a lot of blog posts, and people that will tell you that the binary format of Wasm cannot be understood by the host system, and vice-versa. They’ll say you need to serialise your data into some canonical format and copy your data in and out of WebAssembly’s linear memory. But, that’s rubbish. You just need to understand the binary format, or ABI that WebAssembly uses and that’s easy, because it’s a Linux binary format. If you are integrating your WebAssembly runtime on top of a Linux platform, then this makes getting data in and out of your WebAssembly application easy, or as my old professor in Belfast might say “wee buns”.

Yes, I know, this is a bold claim, but let’s delve into it a little more.

Understanding Byte Alignment

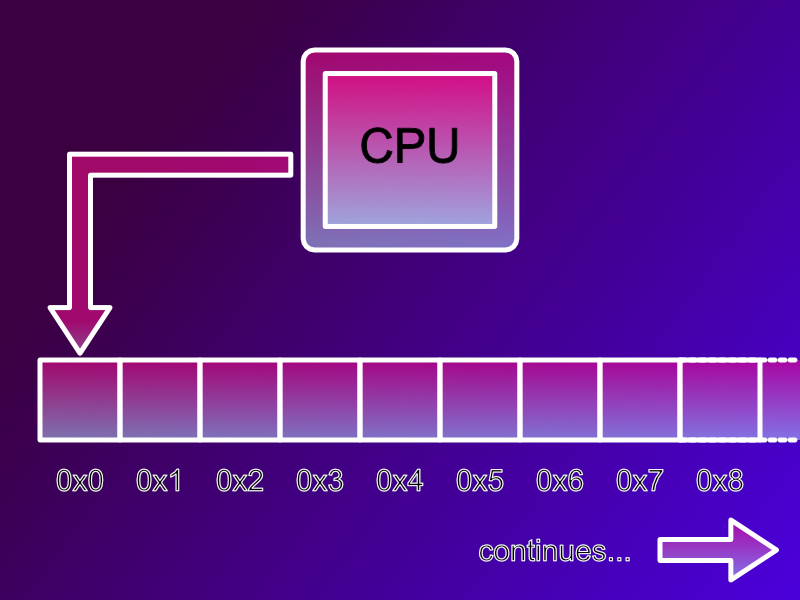

This all starts with the past and understanding byte alignment. Let’s go back to the days of the Sinclair Spectrum and Commodore 64 when 8 bit home computers were common place. These 8 bit machines accessed memory one byte (8 bits) at a time. When the processor wanted to read or write RAM it could read each byte individually.

Along comes the 16 bit era and the Atari ST, Commodore Amiga, Macintosh and IBM PC 8086 machines appear. These are 16 bit machines and when they want to read or write RAM they do so 16 bits (2 bytes) or a “short word”, also know as just a “short”, at a time. However, they can only address the even memory addresses, 0, 2, 4, etc. If you wanted to read a byte at address 3, you’d read two bytes (or a short) from address 2 then extract the single byte you wanted.

These machines had a limitation however, if you wanted to read a 2 byte word stored at memory address 3, and you asked the processor to read a word from address 3 the processor would trap / error. Sometimes this would result in a crash. This was known as a misaligned memory access.

This whole process extends the same way to 32 bit machines, like the IBM PC 386/486/Pentium where they read “words” or 32 bits (4 bytes) at a time, and again for 64 bit machines. Modern machines don’t trap / crash when you attempt a misaligned memory access, the processor and it’s MMU can cope with this, however it slows the processor down.

Working Around Byte Alignment

In C we organise related data together in a structure or struct for short.

typedef struct MyStruct {

uint8_t byte;

uint16_t shortWord;

} MyStruct;

These structures contain members which we will access individually in our code. However, if the struct above was laid out in memory as it is logically shown, there would be a single byte occupying the first location in memory, and a 16 bit short occupying the next two bytes. This would mean that the 16bit short would fall across a byte alignment boundary and hence cause a miss aligned memory access.

MyStruct s = {};

s.shortWord = 42; // should be aligned

To work around these issues the C specification deliberately under specifies what a structure should look like. It specifies that the data should be laid out in order with byte coming before shortWord but that’s about it. This allows compilers to insert padding bytes, if needed to make sure that the members of their structures are indeed byte aligned. This under specification allows the compilers to optimise for the platforms they target. But, it can also cause issues.

The Black Hole Like Gravity of Defacto Standards

Let’s imagine that we’ve got two C compilers from two different vendors. Each C compiler is free to restructure how it represents data in memory. So, a struct produced by compiler A, will look, in memory, completely different from a struct produced by compiler B. But, what if we are writing an application using compiler A, that will link against a library from compiler B?

If both compilers create different physical memory layouts for the same data, then code generated by compiler A will not be able to understand the data structures created by compiler B, and vice versa. This would suck. The need for compiler interoperability exists on almost every operating system in the world.

Nearly every operating system has a kernel written in C. All applications running on an operating system will need to access their OS’ kernel, this means that all the compilers written for that operating system must produce memory layouts which match the memory layout of the compiler that was used to create the kernel.

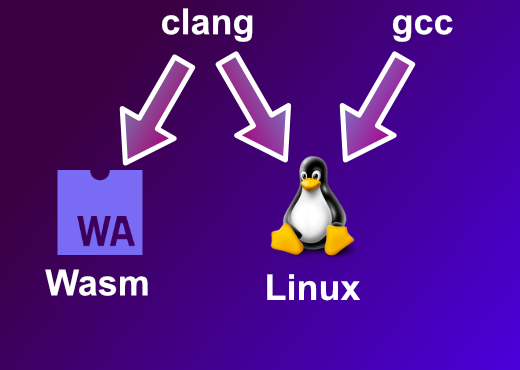

So, on Linux we can compile an application using both clang and gcc. Both of these compilers must adhere to the Linux ABI (Application Binary Interface) specification and produce exactly the same memory layouts.

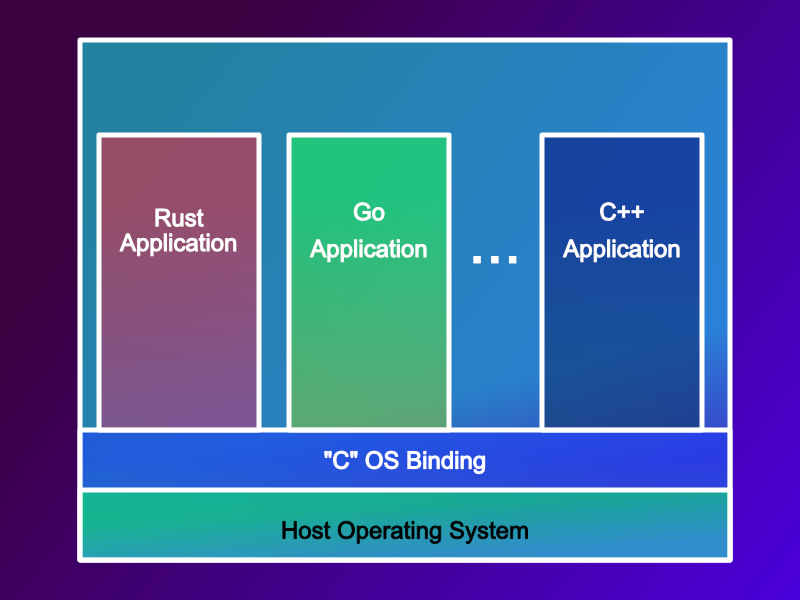

This is true of course for C compilers, but it is also true for every other programming language too.

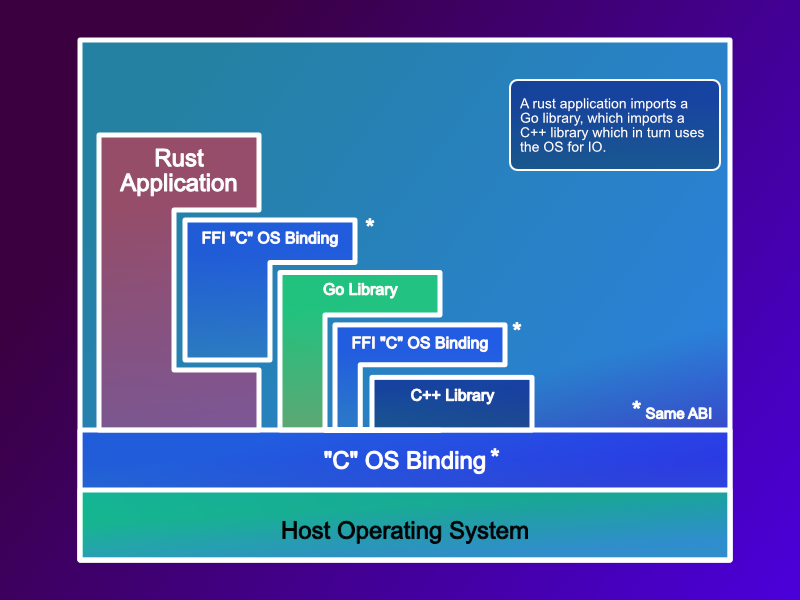

Using Rust? - well at some point it needs to call a C function from the Linux kernel, so that will result in a Rust FFI (foreign function interface) call to C, and that C version must match the version the kernel uses. This also holds true for Go, and every other language we use. It also explains how Rust / Go, etc. provide interoperability, they do it via the C ABI, this allows them to link against the OS, but also with libraries (*.dll / *.so) from other vendors.

This is known as the ABI Black Hole, everything eventually converges on the same in memory layout.

The WebAssembly ABI

Does WebAssembly have an ABI? - Well, not officially… but unofficially it does! You see, the compiler we use to compile C to Wasm is the clang compiler, and the clang compiler follows the Linux ABI. So, the WebAssembly world has inherited a defacto standard ABI - the Linux ABI.

Validating the ABI

To ensure that this is correct I’ve written some C tooling which will allow you to annotate a struct, and then using the field offset macros, it will calculate a “byte map” of a struct. It allows you to visually see the data and padding bytes of a struct. You can find this code on my GitHub page.

We can take a simple structure like this:

typedef struct T8and64BitataTypes {

uint8_t eight;

uint64_t sixtyfour;

} T8and64BitataTypes;

We can use my handy utility to create the metadata description, which is automatically called T8and64BitataTypes_meta, then we can print to the screen. The annotation looks like this:

START_DESCRIBE_STRUCT(T8and64BitataTypes)

DESCRIBE_FIELD(T8and64BitataTypes, eight),

DESCRIBE_FIELD(T8and64BitataTypes, sixtyfour)

END_DESCRIBE_STRUCT;

And then, I’ve a handy utility which can print it out to the console:

showStructure(&T8and64BitataTypes_meta);

I’m writing this blog post on an M1 Mac running MacOS, so that’s an ARM64 platform and it generates a structure which looks like this (I’ve added some automatic detection of platform and compiler):

A small example to show structure packing across platforms

Platform: arm64

Compiler: Clang

structure T8and64BitataTypes[ 16]

eight @ 0 [ 1]:#-------

sixtyfour @ 8 [ 8]:########

It shows the total size of the structure (16 bytes), then in the table below, we get the name of the member variable, and @ and the offset into the structure the member variable is, and the total size of the member variable. Then a graphical depiction of the data and padding bytes. The # represents a data byte, and the - represents a padding byte. So, we can see on an ARM64 platform the compiler has padded the first byte to fit in a 64bit machine word. Which makes sense on an ARM64 platform. I do have access to an Intel Xeon, and when I run the same code on there we get:

A small example to show structure packing across platforms

Platform: x86_64

Compiler: GCC

structure T8and64BitataTypes[ 16]

eight @ 0 [ 1]:#-------

sixtyfour @ 8 [ 8]:########

Even though we are using a different architecture and a different compiler the compilers are padding the same way. We can try this on an ARM32 device too:

A small example to show structure packing across platforms

Platform: arm

Compiler: GCC

structure T8and64BitataTypes[ 16]

eight @ 0 [ 1]:#-------

sixtyfour @ 8 [ 8]:########

We can even try this in WebAssembly:

A small example to show structure packing across platforms

Platform: wasm32

Compiler: Clang

structure T8and64BitataTypes[ 16]

eight @ 0 [ 1]:#-------

sixtyfour @ 8 [ 8]:########

For all practical purposes the padding rules remain the same across clang and gcc and across 64bit and 32bit architectures.

Caution: With Great Power comes Great Responsibility

The major reason folks suggest that you should serialise data into and out of your WebAssembly applications is because of the miss match between the host systems ABI, and WebAssembly’s ABI. But as long as you can understand the WebAssembly ABI you can work around this. This will be easier on some host systems than others, but it is possible. As long as we understand the ABI being used from our compiler of choice (clang) and its relationship to the host system. Of course, for Linux based host systems this is going to be pretty straightforward. For non-Linux systems you will have extra work to do.

Multiple Languages

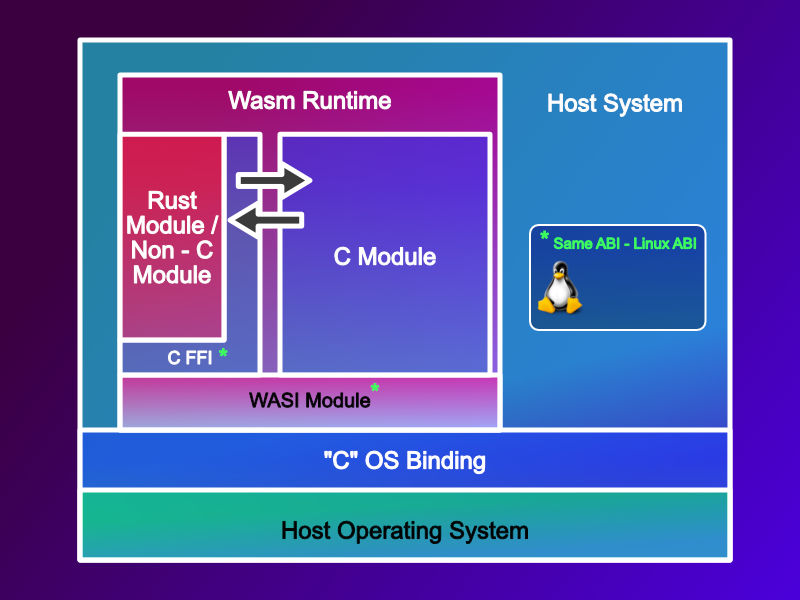

I know what you are going to say, what if I’m not using clang and C? - Right. What if I am using multiple languages, and each language can have its own in memory representation of data, structures, and most commonly encountered, strings. For these languages you would need to use their built in FFI for C.

If you are building a WASI P1 application in C, it will use the WASI interfaces, which are in C and your language of choice will need to use its FFI to invoke and interact with WASI P1.

Share via Copy - The Component Model

If you have the CPU cycles and don’t mind the performance hit, then the Component Model provides an alternative, but this is going to involve copying memory.

Examples of WebAssembly and Host System Integrations

Let’s take a quick look at the practical challanegs of integrating WebAssembly with a host system. I’ve got two systems we can take a deeper dive into.

Linux Host & Wasm Guest

This is probably the easiest to integrate. The biggest challenge is machine word length; WebAssembly 32 or WebAssembly 64 with Linux 32 or Linux 64? – The padding rules remain the same, however the size of a pointer will change, a 32 bit machine has a 4 byte pointer, and a 64 bit machine an 8 byte pointer. If you are aware of this, you can work around it. Later on in this blog post I’ll go into additional detail on how to handle pointers.

Zephyr & Wasm Guest

But it is not all plain sailing. I have heard that Zephyr defines enums with a numerical value smaller than 65,534 as 16 bit (short) variables, and enums with a value larger as 32 bit values. This can cause some issues. It is also possible to work around this with C’s union to ensure that data types have a fixed length, more about that later on in this blog post.

Working the ABI & Sharing Data with Zero Copy

Now we understand the defacto WASM C ABI, we can share information between the Wasm guest and the host directly. We can do this without copying the data, by using a set of shared structures via a single shared header file. There are a few tricks we can use to help us.

3 Key Tips for Sharing Structures Between Host and Wasm Guest

Tip 1 : Use stdint.h

Probably the most important thing to bear in mind is that compilers for different systems can have different binary representations of the base C types : int, short, long, long long etc. The best way to avoid this is to use the stdint.h header file. This defines fixed binary size variables like uint8_t, uint16_t, int8_t, etc. This ensures that all compilers will understand the same binary size of base types.

Tip 2 : Use a union to fix the size

There are some types you may want to use that don’t have a representation in the stdint.h , the enum and pointer size changes I mentioned earlier come to mind. For these situations we can use a union with one of the fixed size data types from stdint.h to ensure that all compilers generate binary representations of the same size.

Tip 3 : Pointers in Linear != Pointers in Host

In C pointers can contain the memory address of some data, or the memory address of a function. In native code these are all just memory addresses, but in WebAssembly they aren’t. Pointers to functions are in fact indexes into a table, and pointers to memory or byte offsets into WebAssembly’s linear memory. The C type system provides enough information to differentiate between the two.

When we pass pointers between the host and the guest systems we need to convert between WebAssembly’s representation and the host systems representation. For memory addresses this involves converting a byte offset to a physical memory address, runtimes like WAMR provide utility functions like wasm_runtime_addr_app_to_native to do this. They can also provide supporting functions to allow pointers to functions to be invoked.

Utilities for Dealing with Pointers and Shared Structures

As most Wasm runtimes are Wasm 32 and for performance reasons may well remain that way for a while, dealing with pointer size changes is going to be a fairly common thing. I’d like to share with you a set of utilities I’ve created that help me deal with sharing structures between Wasm guest and host systems.

Traversing Cross Platform Data Structures

Let’s imagine that we’ve created an application in Wasm which has a set of structures. Both the host (usually 64 bit) and the guest wasm system (usually 32 bit) will want to traverse the data structures present in memory. We’ve a choice, we can either:

(1) Convert the addresses between WebAssembly and host on the fly; this works, but might introduce a performance penalty.

Or

(2) Convert and cache the memory addresses in advance, reducing the need to repeatedly invoke the conversion function on each memory access.

Here the memory usage pattern we typically see in embedded / real time systems actually works in our favour, and option 2 can often be the way to go.

Memory Usage Patterns in Control / Real Time Systems

In most embedded systems, or in fact any system where response time is key, we avoid memory allocation. A call to malloc / free or new and delete is typically not a constant time operation, they can take a lot of time to complete. On top of that in a long running application memory fragmentation occurs, where there might be enough free memory, but it’s broken up in to small chunks across the heap. When this happens, even though we’ve enough free memory for the amount we request in our call to malloc it isn’t available in one continuous chunk, and so our malloc fails.

To avoid this most folks allocate memory before the start of the control loop, then either never do it again, or manually manage memory.

This actually works to our advantage. We can use a double pointer, which contains the host address and the Wasm address. We can then place the data structures into linear memory where both the host and guest can see them, and populate both the host and wasm memory addresses, converting Wasm addresses to host addresses or vice versa. We only have to do this once, at start up.

So, our structure would look something like this:

typedef union TXPointer { // fix pointer size to 8 bytes

void* ptr;

uint64_t asUint64;

} TXPointer;_

typedef struct TCachedXPointer {

TXPointer wasm;

TXPointer host;

} TCachedXPointer;

Then we could use some macro trickery, so that we can write code which would automatically retrieve the right pointer, regardless of it is run on the host or guest (wasm) :

#ifdef __wasm__

#define XPTR(A) ((A).wasm.ptr)

#else // ! __wasm__

#define XPTR(A) ((A).host.ptr)

#endif // __wasm__

So, if we wanted to have a pointer to a uint32_t we could write that like this:

uint32_t value = 42;

TCachedXPointer cp = {0};

XPTR(cp) = &value;

But reading the pointer value requires casting it, which is a pain:

printf("value is %u\n", *(uint32_t*)XPTR(cp));

It’s ok for simple structure, but if we were detailing with a more complex data structure it quickly becomes very very cumbersome. But I think there is something we can do about that!

A Very C like Template

In C++ we would deal with this situation using a template. They are a fantastic way to create data structures which can handle typed data safely, but without the inherit casting. However, when you look really closely at a C++ template, it is basically a pre-processor macro which generates the data structure for you. So, it should be possible to apply a similar technique to C!

You know you are on to something, when someone else beats you to it. Ian Fisher had the same thought about 5 years before I did, and he was kind enough to blog about it. I’ve not met Ian, but I owe him a thank you. I really recommend you check out his amazing blog post here.

If you want to skip his blog post, I’ll give you the elevator pitch: We can use pre-processor macros to generate data types which have type safe member data. Essentially, we use the pre-processor to replace our void* with typename*, where typename is the type you need to store.

You can find the header file for this on my github page here. But it looks a little like this:

#define CONCAT(A, B) A##B

#define MONIKER _XPLATFORM

#define CREATE_XPLATFORM_PTR_TYPE(payload_type, new_type_name) \

typedef union new_type_name { \

uint64_t u64; \

payload_type* ptr; \

} new_type_name

#define CREATE_CACHED_XPLATFORM(payload_type, name) \

CREATE_XPLATFORM_PTR_TYPE(payload_type, CONCAT(payload_type, MONIKER));\

typedef struct name {\

CONCAT(payload_type, MONIKER) wasm;\

CONCAT(payload_type, MONIKER) host;\

} name

#define XPTR_SET_NULL(A) (A).wasm.ptr = NULL; (A).host.ptr = NULL

#ifdef __wasm__

#define XPTR(A) ((A).wasm.ptr)

#else // ! __wasm__

#define XPTR(A) ((A).host.ptr)

#endif // __wasm__

It is nowhere near as pleasant to write as a template definition in C++, but it does provide addition type safety in C. So, this means that if we want to access a uint32_t pointer, we can do it as follows. First we define it:

#include <stdio.h>

#include "crossplatformpointer.h"

CREATE_CACHED_XPLATFORM(uint32_t, xuint32Ptr);

Then in our function we use it:

uint32_t val = 42;

xuint32Ptr u32pr;

XPTR_SET_NULL(u32pr);

XPTR(u32pr) = NULL;

printf("A small example to show cross platform pointers\n");

XPTR(u32pr) = &val;

printf("val is %u\n", *XPTR(u32pr));

*XPTR(u32pr) = 52;

printf("val is %u\n", val);

Using this technique, we can create data structures in a WebAssembly instance’s linear memory and access them in C safely from both the host (native) and the guest (WebAssembly). - That’s pretty cool. This way we can share data across the boundary without serialisation, without additional copying - which saves us precious CPU cycles we can use to do our application logic.

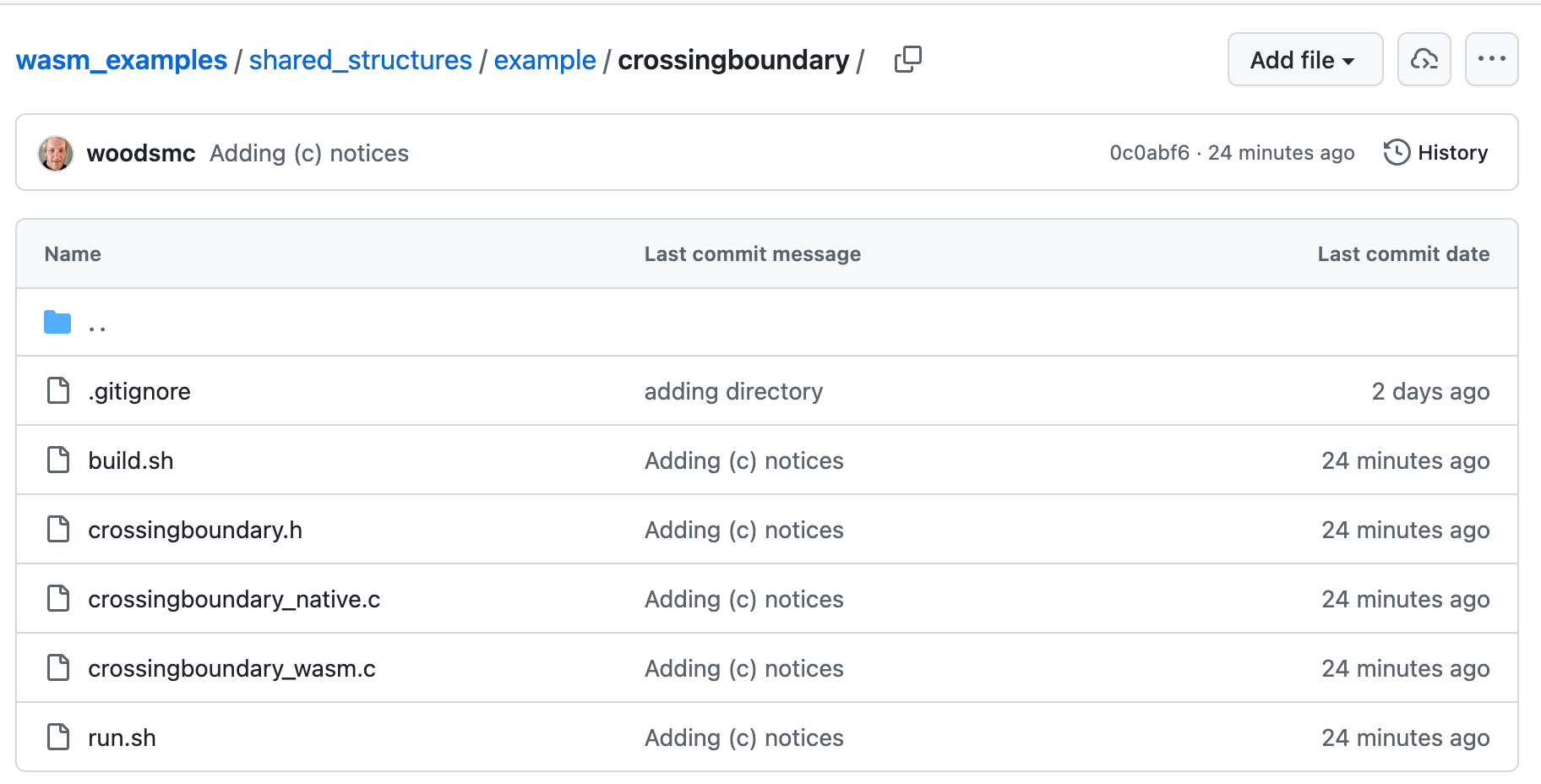

A Working Example : No Serialisation Required

Over on my GitHub page I’ve got a working example of how to share data and iterate over a data structure from both WebAssembly and host. No serialisation required.

The Shared Data Structure

First, we define a really simple linked list:

// crossingboundary.h

#pragma once

#include "crossplatformpointer.h"

typedef struct TLinkedListNode TLinkedListNode;

CREATE_CACHED_XPLATFORM(TLinkedListNode, XTLinkedListNodePtr);

typedef struct TLinkedListNode {

XTLinkedListNodePtr next;

uint32_t value;

} TLinkedListNode;

The WebAssembly Population of the Data Structutre

Then inside a WebAssembly module we create the linked list and populate it with data. We do this by creating a function which can append (add) to the linked list:

// corssingboundary_wasm.c

#include "crossingboundary.h"

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

//...

XTLinkedListNodePtr addToList(XTLinkedListNodePtr head, uint32_t value) {

XTLinkedListNodePtr newNode = {0};

XPTR(newNode) = malloc(sizeof(TLinkedListNode));

if (XPTR(newNode) == NULL) {

printf("Failed to allocate memory for new node\n");

return newNode;

}

XPTR(newNode)->value = value;

XPTR_SET_NULL(XPTR(newNode)->next);

if (XPTR(head) == NULL) {

printf("The list was empty, this node is the first node %u\n", value);

return newNode;

}

printf("Adding node with value %u to the front of the list\n", value);

XPTR_SET(XPTR(newNode)->next, head);

printf("newNode->next is %p\n", (void*)XPTR(XPTR(newNode)->next));

return newNode;

}

Then we create a head node and populate it with data:

// corssingboundary_wasm.c

//...

XTLinkedListNodePtr head = {0};

for(int i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

head = addToList(head, i);

printf("head is %p\n", (void*)XPTR(head));

}

// ...

Then we can invoke a host function to print out the list:

// corssingboundary_wasm.c

#include "crossingboundary.h"

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#define WASM_IMPORT(A, B) __attribute__((__import_module__((A)), __import_name__((B))))

WASM_IMPORT("example", "printList") void printList(XTLinkedListNodePtr* head);

//...

XTLinkedListNodePtr head = {0};

for(int i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

head = addToList(head, i);

printf("head is %p\n", (void*)XPTR(head));

}

printf("Calling printList in the native code\n");

fflush(stdout);

printList(&head);

fflush(stdout);

printf("Returned from printList in the native code\n");

The Host Code to Process the Data Structure

In this example I use a WAMR native library as a quick way to provide a host function. This native library provides a single function to the running WebAssembly code - printList.

The printList function receives a pointer to the head cross platform pointer. However we can’t use it straight away. It contains the WebAssembly linear memory address but not the native / host memory address. We have to iterate over all of the cross platform pointers (the next members) of the linked list and add a native / host memory address. To make this easy, there are some new macros I’ve added to our crossplatformpointer.h:

// crossplatformpointer.h

#pragma once

#include <stdint.h>

//....

#define XPTR_SET_NULL(A) (A).wasm.ptr = NULL; (A).host.ptr = NULL

#define XPTR_IS_COMPLETELY_NULL(A) ((A).wasm.ptr == NULL && (A).host.ptr == NULL)

#define XPTR_IS_HOST_NULL(A) ((A).host.ptr == NULL)

#define XPTR_IS_WASM_NULL(A) ((A).wasm.ptr == NULL)

#define XPTR_GET_WASM_ADDR(A) ((A).wasm.u64)

#define XPTR_SET(A, P) (A).wasm.ptr = (P).wasm.ptr; (A).host.ptr = (P).host.ptr

#define XPTR_PRINT(A) printf("XPTR: wasm.ptr=%p host.ptr=%p\n", (void*)(A).wasm.ptr, (void*)(A).host.ptr)

#ifdef __wasm__

#define XPTR(A) ((A).wasm.ptr)

#else // ! __wasm__

#define XPTR(A) ((A).host.ptr)

#define XPTR_RESOLVE_HOST(module_inst, A) if( (A).wasm.ptr && !(A).host.ptr ) { (A).host.ptr = wasm_runtime_addr_app_to_native( (module_inst), (A).wasm.u64); }

#endif // __wasm__

Then I’ve provided a simple function to update the linked list:

// crossingboundary_native.c

//...

void update_native_addresses(wasm_module_inst_t module_inst, XTLinkedListNodePtr* head) {

XTLinkedListNodePtr* current = head;

while (!XPTR_IS_COMPLETELY_NULL(*current)) {

XPTR_RESOLVE_HOST(module_inst, *current);

current = &XPTR(*current)->next;

}

}

When we get called to print the list out, I update the native addresses then I can iterate over the list easily and print out results:

// crossingboundary_native.c

//...

void printList(wasm_exec_env_t exec_env, XTLinkedListNodePtr* head) {

printf("Native -- Printing list:\n");

wasm_module_inst_t module = wasm_runtime_get_module_inst(exec_env);

update_native_addresses(module, head);

fflush(stdout);

XTLinkedListNodePtr* current = head;

XPTR_PRINT(*current);

while (XPTR(*current) != NULL) {

printf("Node value: %u\n", XPTR(*current)->value);

current = &XPTR(*current)->next;

}

fflush(stdout);

}

The code for this is all available on my GitHub, you can find the example here.

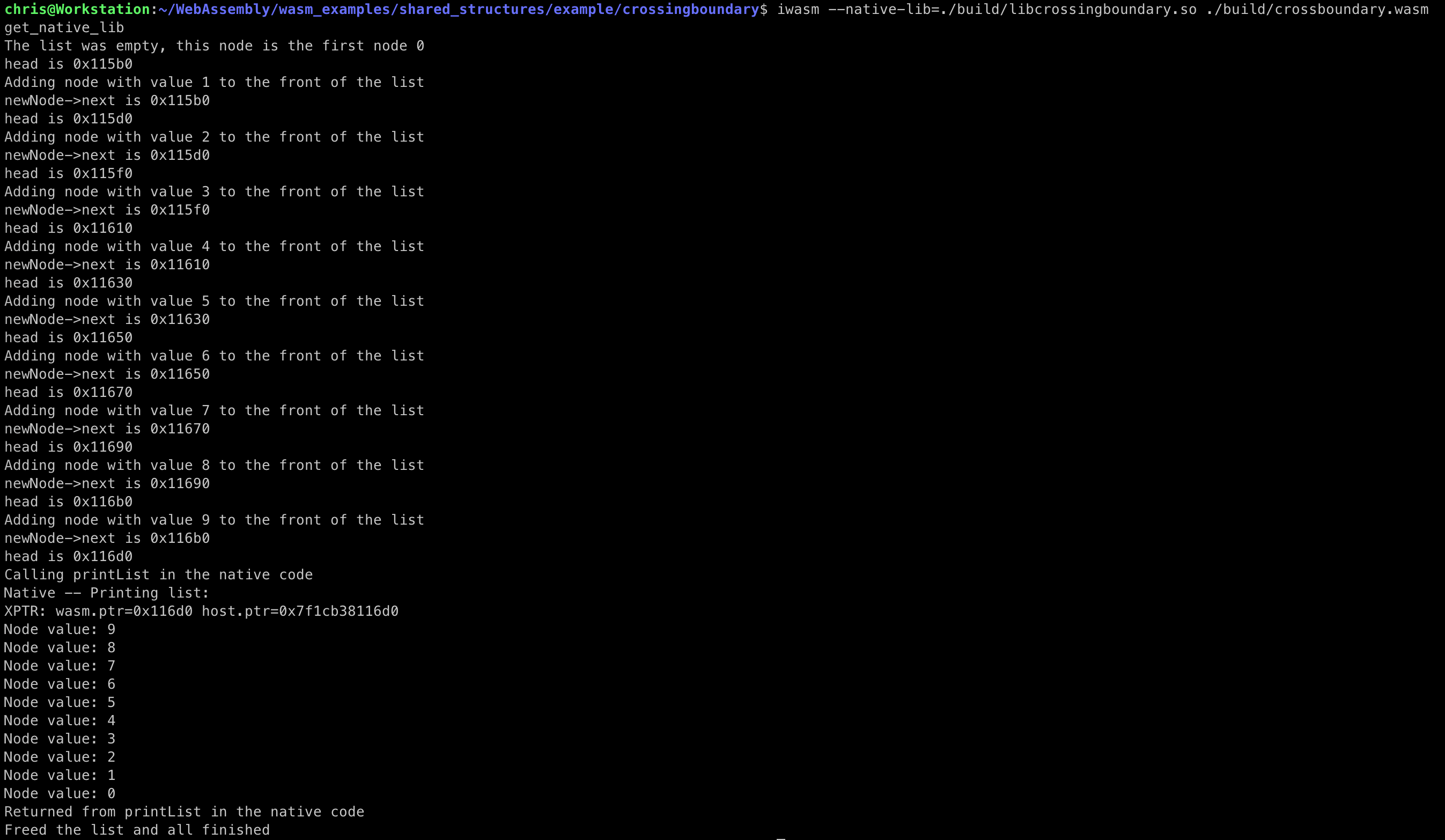

Once you build the native and WebAssembly sides, you can invoke it as follows:

iwasm --native-lib=./build/libcrossingboundary.so ./build/crossboundary.wasm

And it shows the linked list being populated by 32bit WebAssembly code and then iterated over via some host code:

That’s how you share data structures between WebAssembly code and the host / native C world without needing to copy data and allowing both code bases to interact with the structures directly.